For a small mountainous country divided between Italian, French and German [and Latin] speakers, Switzerland punches well above its weight in terms of design. Univers, Frutiger, and the mighty Helvetica are all Swiss; HR Giger, the creative brain behind the look and feel of the Alien films, was Swiss; even the Swiss flag is neatly minimalist. If you’re designing in Switzerland, you’re standing on some very large shoulders.

Two such designers are English duo Vanessa Bradley and Martin Spendiff. As VEEB, the duo have been creating devices sometimes simple, sometimes complicated, but always beautifully clean. We caught up with Martin late last year to find out what they’re all about.

HACKSPACE: Are you designers first and foremost, or engineers, or something else? I ask because your projects are unusually pretty. A lot of Raspberry Pi projects have wires sticking out and bare PCBs exposed, but yours always look so clean.

VEEB: We aren’t. Our backgrounds are IT (Vanessa) and Mathematics (Martin).

The physical form that a project ends up taking is one of the most challenging bits (for us, it is anyway).

Appearance is often tied to the workflow. The ‘cyberdeck’ we made a while ago was a good example. It’s the 80/20 rule. Getting to a working version was quick and easy, but it took about another year of experimenting with tools that turned a novelty into something that we found genuinely useful. It now gets used for emailing (NeoMutt), writing (Neovim) and compiling MicroPython for some of the hardware we sell.

HS: What first drew you to using Raspberry Pi?

VEEB: When it first came out, it was excitement at such a small and affordable tool for doing things with, but, over time, it became much more about the community. We tried using

The real epiphany was the Pico microcontroller, which made us suddenly look at things and think ‘we could make one of those.’ It also taught us to be better at using tools that were more suited to addressing the thing you’re trying to do. There was a case, when we were building something recently, when we realised that the best thing to use was just a simple switch… no microcontrollers, no relay, just a one-dollar switch. I suppose that it’s a version of ‘just because you can, doesn’t mean that you should.’

r/Quotes subreddit

HS: You do a lot of upcycling, adding new functionality to machines that should, by rights, be obsolete. What is it about old objects that inspires you to work with them?

VEEB: Three reasons:

Maybe it’s an age thing, but the constant cycle of upgrading means that you can end up chasing the latest and greatest thing while ignoring what went before. A lot of innovation is working around limitations that exist at the time, and there are some really smart ideas contained in old objects. Those smart ideas should be augmented with new tools, not abandoned.

There’s also an element that is just about waste. There’s an old video of someone making a toaster from scratch, and it really underlines how much effort goes into making ‘things’.

Blade Runner was a really cool film. The retro-futuristic tech in that was pretty spectacular. If we can make things that have that aesthetic, we’d be more than happy.

HS: Everything you make seems to do one thing, and one thing well. Is that on purpose?

VEEB: We buy into the first item of the Unix philosophy which was written in a Bell System technical journal back in 1978:

“Make each program do one thing well. To do a new job, build afresh rather than complicate old programs by adding new ‘features’.”

Maybe our version would include adding new features to old things that would otherwise be redundant, but that’s the general idea.

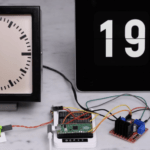

HS: You rehabilitated a German railway clock using a ferrite antenna attached to a Raspberry Pi Pico. That’s way beyond most people’s ability. Where do you start with knowing how to do this? Is this deep ham radio knowledge?

VEEB: Definitely not. That was a rabbit hole that appeared upon wondering how the clocks at train stations worked. We live in a country that is obsessed with things being on time, and just ended up talking to the people that have an encyclopaedic knowledge about that stuff.

Pick any subject and, no matter how obscure it is, there’s most likely a forum on the internet, full of experts who are keen to grumpily share their expertise.

HS: Also, it’s incredibly cool, but most people wouldn’t bother with the cool part. What inspired you to take the time from a (presumably Cold War) radio signal coming from an atomic clock?

VEEB: It’s probably the uncool part! The clocks were really interesting to us because they were gorgeous objects, and there was a time signal there, so we just needed the ‘glue’ to join that signal to these redundant old things to get them rejuvenated and useful again.

HS: You document your build processes on GitHub. Do you get people adding improvements/suggestions to the way that you do things?

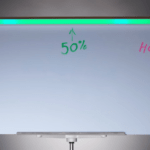

VEEB: The best bit about adding things on GitHub is when people use your idea to do something new

or better.

There has been more than one person that has made massive progress bars for their classroom. Knowing that people are looking at your code is a good way to make sure it’s not too terrible.

HackSpace magazine issue 75 out NOW!

Each month, HackSpace magazine brings you the best projects, tips, tricks and tutorials from the makersphere. You can get HackSpace from the Raspberry Pi Press online store or your local newsagents.